Some constitutional cogitations from Cardiff

The aggressive Anglocentric British nationalism of the post-2016 period doesn't work for the wider UK, especially Northern Ireland. I looked at why, and what might instead.

Background to this post

On 22 November I was invited by the First Minister of Wales, Rt. Hon. Mark Drakeford MS, to give a lecture at the Hadyn Ellis building at the University of Cardiff. It is part of a series of lectures he and his team are hosting on the constitutional future of the United Kingdom.

The text of my talk is published below. At some point a video of the event, including the question and answer session afterwards, will be published online.

For now, here is the text of the lecture. (As always, a check against delivery caveat when the video comes out).

A point on timing. This lecture was delivered exactly one month ago today. It was delivered the day before the Supreme Court ruling that the Scottish Parliament did not have the power to hold an independence referendum. It was also delivered before the launch of the report containing proposals for constitutional reform by the former Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Gordon Brown, and before the publication of the interim report of the Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales. However none of these developments alter the fundamental arguments in the lecture.

Text of lecture - check against delivery

I am really honoured to be here with you this evening. Thank you for the privilege.

[audience specific introductory remarks omitted]

My main message tonight is aimed at those who want to see a reformed, multinational UK.

Your moment might well be coming.

But meaningful, durable reform is a lot harder than it might look.

And it might be the last chance for it, given the strength of forces on each side:

those who wish to bring the UK in its current form to an end;

and those who wish to roll back devolution in favour of a much more singularly British, unitary form of Government.

You wouldn’t start from here: legacy of the last decade

Let’s start by looking at the situation a decade ago in 2012. (This was when I was working on the constitutional brief in Whitehall).

As Leighton Andrews of this parish has observed, we’d just had Danny Boyle’s opening ceremony for the 2012 Olympics.

This was what Leighton called “the emotional and cultural high point” of what he called “progressive unionism”: confident, respectful, inclusively multinational.

Although a referendum in Scotland had been conceded and agreed following the SNP landslide of 2011, support for independence was so low – hovering between 25 and 33 per cent – that few seriously thought the UK was going to break up.

Indeed, the agreement to the referendum was seen as a confident and respectful acknowledgement of Scotland’s participation in a voluntary union.

I also remember pointing out to David Cameron the extraordinary statistic that support for the Union in Northern Ireland was even higher than in Scotland, with 65 per cent, as against 17 per cent for unification. The Executive in Belfast was in one of its longest periods of continuous existence. Relations between London and Dublin were strong.

The one poll done in Wales during that period found 3 per cent support for independence, rising to 10 if Scotland left. Wales had continued on its path of gaining losers’ consent following the division of 1997, and was seen, from the outside anyway, to be working well.

No one was seriously contemplating leaving the EU: it remained, for the Coalition, as for John Major’s Government, a case of managing querulous backbenchers.

Inter-governmental relations were decent. The Joint Ministerial Committee occasionally met, and, while I don’t want to rose-tint the past, it sometimes even had useful discussions.

Much of the Coalition’s constitutional efforts (other than on the Scotland campaign) were spent trying to improve things in England’s regions, (though the chosen mechanism, City Deals, seemed to involve raising money from local areas and giving it back to them with huge strings attached in return for relatively tiny freedoms and small amounts of cash, and calling it decentralisation).

You wouldn’t start from here: where we are now

Ten years on, the only unchanged feature from that landscape is that Whitehall and English localities are still wrangling over pitiful amounts of money and the devolution of weak powers. Whitehall still has more than one hundred central ‘pots’ or funds, including, and I am not making this up, one for removing chewing gum in local areas, and another for improving public toilets.

But other than that, everything else has changed.

What the whole of the UK now has in common with the situation in England is that the constitution is stuck.

And, particularly in Scotland and Northern Ireland, it is stuck in a tense and polarising way.

In Scotland, the 45 per cent vote for independence has turned into a floor, not a ceiling, for independence.

Now, independence is the all-consuming issue.

One side shouts: “you had your chance in 2014”.

The other yells back: “but Brexit!”.

And round we go again.

Northern Ireland is definitely stuck and tense, something I will return to later, at the organisers’ request.

Is Wales stuck? You tell me and I hesitate to comment in front of this audience. Again, from the outside, things look relatively stable.

Devolution is doing its job: Wales can do things differently in certain areas from a Westminster Government that doesn’t have a majority here.

First Minister of Wales Mark Drakeford spoke of a UK Government “hostile to devolution”

But I can’t help but be struck by the remark by the First Minister in July last year that he considered, for the first time this century, we had a UK Government in his words “hostile to devolution”.

And I can’t help but note that the excellent Leighton Andrews article I cited earlier is entitled “The Forward March of Devolution Halted”.

And across the UK, inter-governmental relations have certainly been scratchier.

So what is going on?

Centralising tendencies: it’s hard to let go

Part of it is to do with the enduring strength of centralising forces in the UK.

The groundhog day debate and reforms around localism in England under Labour, Coalition and Conservative Governments over the past 20 years prove this.

So too does the fact that devolution changed Government everywhere in the UK – except Whitehall.

London still struggles with devolution, as we saw in the pandemic.

But much more fundamentally than that, we now have three competing visions for the future of the UK.

The first vision is simple enough: to bring it to an end through independence (or unification, in the case of Northern Ireland). That doesn’t – yet – have the numbers to achieve its objective.

The second is the vision of an increasingly devolved UK: the one architected in the late 1990s and now seeking renewal via vehicles such as Mr Brown’s commission and the one under the leadership of Lord Williams and Professor McAllister. I will return to the challenges facing such efforts at the end of this talk.

The third vision receives far too little attention given its strength in Westminster.

It has been driving much of the constitutional redesign of the UK since the 2016 vote to leave the EU.

This is sometimes called muscular unionism, or – incorrectly – English nationalism.

Anglocentric British nationalism: a clunky phrase for a powerful force

Although it’s a clunky phrase, a better description of it is one I picked up from the former Labour Cabinet Minister John Denham, though he denies authorship.

It’s Anglocentric British nationalism.

And here are four characteristics of it:

First, it considers that there is really only one nation and it is a British one. Westminster sovereignty is all; hence the hostility to the EU. It’s majoritarian: for example, it doesn’t matter if whole chunks of the UK don’t buy into its form of Brexit, because it has the numbers to face down inconvenient dissent. That those numbers are drawn largely from England makes it Anglocentric;

Second, for the Anglocentric British nationalist, devolution is, in Boris Johnson’s word, a “disaster”. There shouldn’t be real alternative centres of real power to Westminster. Sporting and cultural national identities are fine, but not real power. For as long as devolution cannot be reversed, it must be contained. However, in the words of Lord Frost, devolution can “evolve back”, as the Johnson Government showed with the UK Internal Market Act;

Third, Anglocentric British nationalism pushes back on the idea of the UK as a voluntary union. It talks of the UK as a unitary state – correct in legal terms but politically highly contested, including here in Wales. That is why Anglocentric British nationalism refuses not just the present demands for another referendum in Scotland, but to engage in any discussion as to how and when another one might be held;

Finally, there is an inherently transactional nature to it. It is happy to remind the rest of the United Kingdom not of the joys of partnership, but of the costs of leaving. For that reason, I sometimes call it ‘know-your-place unionism’.

Anglocentric British nationalism successfully secured a hard Brexit for Great Britain.

Its record in driving the devolution agenda is more mixed.

Its symbolic high point, so far, was the refusal of Liz Truss to speak to the devolved administrations’ leaders for the entire duration of her short premiership.

The new administration, thankfully, seems less interested in this type of approach.

But Anglocentric British nationalism is still a powerful force.

As a result, devolution is no longer a one-way street, if ever it was.

It can evolve back, and some people want it to.

And this vision of the UK’s future, whilst not particularly popular right now, will not go away.

And it still matters, particularly with regard to the paralysis in Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland: where Anglocentric British nationalism doesn’t work

Anglocentric British nationalism has been, and remains, a disaster for Northern Ireland.

Contemporary Northern Ireland is based on three things.

First, affirmation of its legitimate place as an integral part of the United Kingdom, but with a right to leave it and join the rest of Ireland, depending on the majority’s will. That was unionism’s great triumph of 1998: acceptance of the legitimacy of the Northern Ireland state by plebiscite throughout the island. But that acceptance depended on compromise.

Second, a key part of that compromise was smooth economic and social relations with the rest of the island of Ireland, reflecting the traditional minority’s desire for as close ties as possible.

Third, and - again - a part of this compromise, power-sharing, devolved Government based on cross-community support.

Anglo-centric British nationalism, and the form of Brexit it gave rise to, crashes up against all three of these pillars of contemporary Northern Ireland.

First, it imposes a view of British sovereignty that is at odds with the 1998 Agreement. The Protocol Bill, that article of faith among Anglocentric British nationalists, states the supremacy of the 1800 Act of Union.

But, as Dr Andrew McCormick, who led for the Northern Ireland Civil Service on Brexit, has written, under the 1998 Agreement, endorsed by referenda on both sides of the Irish border, supremacy is given to the people of Northern Ireland, not to a 222 year old statute, which, under the Diceyan interpretation of the constitution so beloved of Anglocentric British nationalists, has no particular standing above the 1998 Agreement or other statutes in general.

Under the Agreement, the people of Northern Ireland have the right decide whether they want to remain in the United Kingdom or join an all-island state.

For Dr McCormick, that means that Mrs Thatcher’s totem that Northern Ireland is “as British as Finchley”, recently re-stated by the Foreign Secretary using his own constituency in North Essex, is a nonsense.

People in North Essex do not have the right to join another state, or to hold the passport of another country. There are no joint institutions with another sovereign state responsible for parts of the governance of North Essex. All of these things, by treaty and Parliamentary statute, are in place for Northern Ireland.

The 1998 Agreement is one of the foundational documents of the modern UK.

It explicitly acknowledges that the UK can be broken up, and that some of its constituent parts should have highly exceptional forms of local administration.

It is highly unusual, as some unionists point out, for a state to provide for its own breakup. But the United Kingdom does.

Once that principle has been established, everything else is a matter of degree.

The simplicity of Anglocentric British nationalism cannot be accommodated within this complex mosaic.

Second, withdrawal from the Single Market completely changes the nature of North-South relations.

The 1998 Agreement did not mention the EU because it did not need to. The entry of both the UK and the Republic of Ireland into the Single Market in 1993 transformed economic relations on the island, particularly in border areas, even before the ceasefires and the removal of border security apparatus.

Crucially, as well as reducing trade friction on the island, joint single market membership on the island was a significant cultural and economic moment.

As John Hume pointed out repeatedly at the time, the reduction in the emphasis on binary national identity mattered hugely. The sense that being primarily British or Irish was of less importance in the age of greater European integration was profoundly important to the historically minority nationalist community.

Along with the removal of discrimination against Catholics in the 1970s, and the introduction of power sharing in 1998, joint participation in the European Single Market with the rest of Ireland was one of the three reasons why Northern Ireland’s traditional minority community reconciled itself to the Northern Ireland state and voted overwhelmingly - even if some of its leaders won’t say it out loud - to recognise its legitimacy.

The shock at the removal of the single market - without consent - is still palpable in this community.

Finally, given this, Brexit, and particularly withdrawal from the Single Market, was a fundamental change in the governance of Northern Ireland.

History would suggest that fundamental change in Northern Ireland is best done, as in 1998, with cross-community support.

But cross-community support was never, could never, and will never be given for Brexit.

Inevitably, the subsequent attempts to exempt Northern Ireland from aspects of Brexit to reduce the impact on cross-border relations has led to the opposite problem: the withdrawal of consent for power sharing in the unionist community.

All this has proved is that, in the words of Tom McTague of The Atlantic, (a writer not unsympathetic either to Brexit or to Northern Ireland’s unionists) Brexit has led to a set of problems in Northern Ireland that “cannot be solved, only managed”.

That means there are no easy answers, and no perfect one. So what to do?

Stronger local leadership must be part of the answer. But tonight I want to look at what the UK Government, as the sovereign power, should think about.

First, the UK Government must recognise Northern Ireland for as it now is, rather than what it might appear doctrinally in a simplistic, post-Brexit, sovereignty first way.

The lead of unionist parties over nationalists in first preference votes at May’s Assembly elections could fit into Windsor Park stadium, one of international football’s smallest venues.

Both unionism and nationalism are now minorities. The future will be decided by the non-aligned.

At the moment, the non-aligned break decisively for the Union, were there to be a referendum on unity.

But they do not break for sovereignty-first British nationalism.

Northern Ireland used to vote this way.

In 1987, in the first general election after the Anglo-Irish Agreement which unionists reviled for giving Dublin a consultative role in Northern Ireland, unionists implacably opposed to the deal won more than 55 per cent of the vote.

Now polls suggest that if the Assembly is to remain moribund, 60 per cent support some form of role for the Irish Government.

Moreover, a clear majority in the Assembly were returned last year on manifestos to support some form of Protocol arrangements.

Unionism may hate the Protocol, and that matters.

But political unionism is no longer a majority, and that matters too.

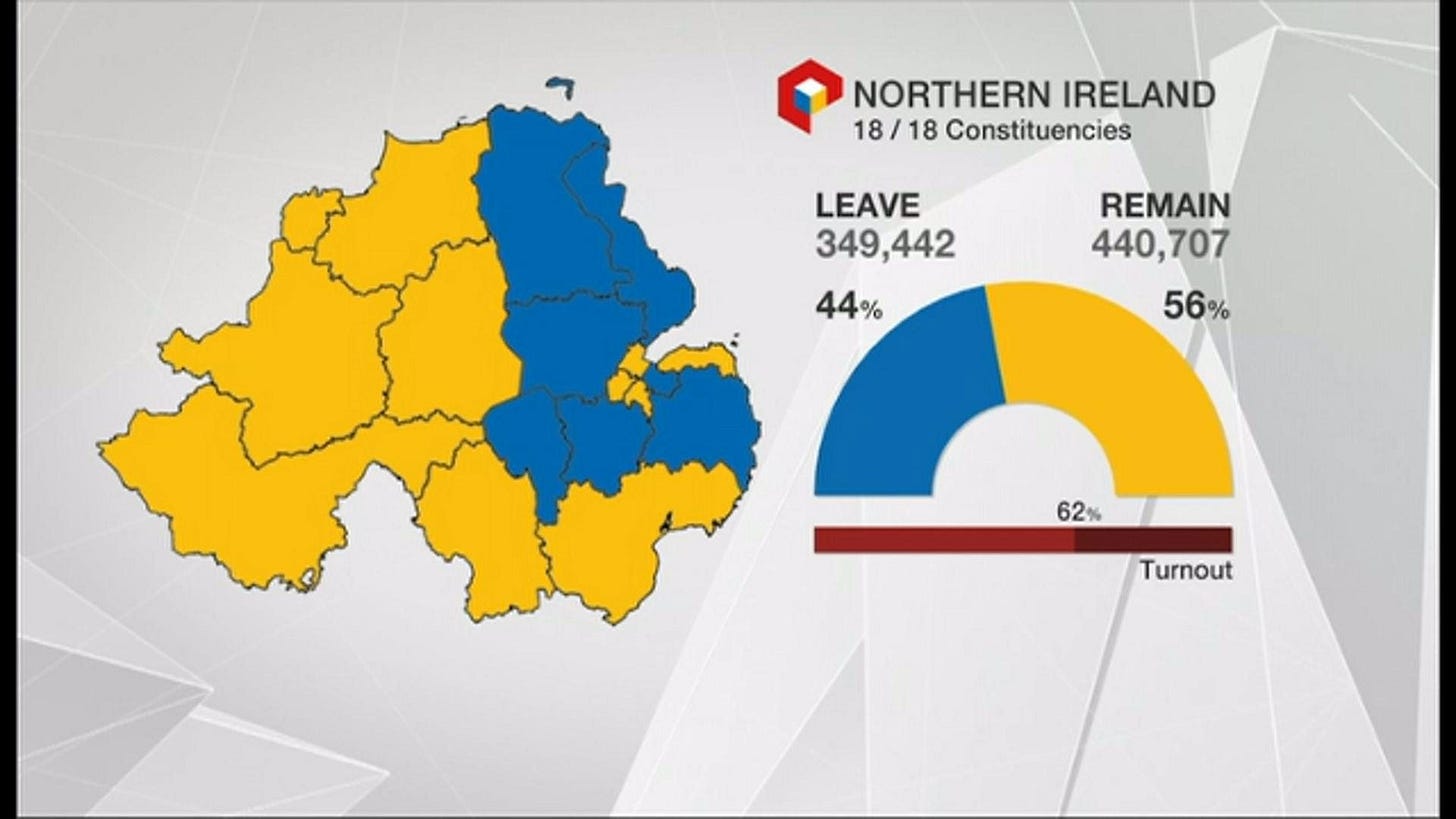

The Brexit vote in Northern Ireland. Note that not a single border area voted to leave. Indeed, at present, no constituency touching the border is represented at Westminster by a unionist.

The present ‘majority’ in Northern Ireland, insofar as there is one, expects to remain in the UK for some time to come. It wants governmental arrangements that will work, for however long that is.

But this ‘majority’ is perfectly happy for Northern Ireland to be treated differently from the rest of the UK, and indeed sees some advantages to such arrangements.

So Northern Ireland is not North Essex, and doesn’t want to be.

But this does not, of course, solve the current problem of unionist consent, the piece that is currently lacking.

So the second part of the answer, which may seem unsatisfactory and incomplete but I think is important, is about process.

Process matters.

In an outstanding paper for the UK in a Changing Europe think tank in August, Sir Jonathan Stephens, recently retired Northern Ireland Office permanent secretary and key protagonist in many of the key negotiations of the past quarter century, wrote that “the process around the Protocol has been fundamentally flawed because the key players who need to accept and work with the outcome – the parties in Northern Ireland – have never properly been involved”.

He noted that in the run up to the Agreement 25 years ago, the advice to British Ministers was that the process they oversaw was far more important that any specific solutions. And an important part of that process was, despite clear and obvious differences, London would treat Dublin as a partner, not as an opponent.

From this sort of inclusive process, solutions might emerge. Without it, we cannot know what solutions will stick.

Third, the problem must be treated now as a Northern Ireland issue first and foremost, rather than a consequence of negotiations between the UK and the EU.

Trade is, of course, the major part of the technocratic dimension. And that’s a London to Brussels issue.

But we have to remember that Brexit fundamentally ruptured Northern Ireland politics because it removed the Europe-wide framework where binary national identities mattered less.

You cannot solve a political crisis about identity, consent, all-island relations, relations between the islands, relations between communities, and much more – with chilled meat protocols or reciprocal arrangements for veterinary standards.

The EU will continue to have concerns about the integrity of its single market. But it’s increasingly obvious it will want to support something that could command genuine cross party support in Northern Ireland.

Fourthly, and this is the biggest hurdle to overcome, all this requires a rebuilding of trust. Over the course of the last year, trust in the UK Government to deal with the protocol, as measured by Queen’s University, has nearly doubled – to 7 per cent.

It is not hard to figure out why trust is so low. We had:

a Secretary of State during the referendum campaign assert that leaving the EU would not affect arrangements in Northern Ireland;

a Prime Minister in 2019 assert that his deal was similarly benign for Northern Ireland;

and a later Secretary of State on New Year’s Day in 2021 assert there was no sea border just as film footage of new inspections were being broadcast on TV the very same day.

Really substantive progress, in my view, is impossible for as long as the line from London remains that Brexit is no big deal when it comes to Northern Ireland.

Beyond Northern Ireland: challenges for the UK’s reformers

It may be, therefore, that change in approach might need to await a change of Government, (though on the other side of the Irish Sea the seismic prospect, though not the inevitability, of a Sinn Féin led Government in Dublin from 2025 might act as an incentive for more urgency).

In any case, I hope that the example of Northern Ireland – unique as it is, shaped by a tragic and brutal recent history thankfully absent from the rest of the United Kingdom – is enough to show that a simplistic application of post-Brexit, sovereignty-first, Anglocentric British nationalism is not the right approach for at least one part of the UK.

The question now arises as to what’s next for the rest of the United Kingdom.

In that context, let me return to the second group seeking to shape the future of the UK: the reformers.

I detect great excitement in this community that, with the polls as they are, and reformers on the brink of outlining new plans for a reconstituted UK, tensions within the territorial constitution will dissipate in the next Parliament.

And that will sweep away Anglocentric British nationalism from its position of influence within the UK Government.

And in doing so, it will weaken support for separation, especially in Scotland.

That may be so.

But looking beyond that timeframe, it is also credible to think of this as the last chance for meaningful reform of the UK in its current form.

Consider this outline of the future.

There’s a change of UK Government in 2024.

A Labour or Labour-led Government introduces constitutional reforms designed to strengthen devolution.

A Westminster Conservative opposition, hardening against devolution out of office, as it did over Europe after its 1997 defeat, opposes those reforms and pledges to reverse them.

The economic inheritance of the new Government proves too tricky: it is short-lived and in the late 2020s or early 2030s a form of Conservatism that is much more anti-devolution than before comes into power.

The argument of 2024 in Scotland (and possibly Wales) that you don’t need independence to protect you from a Conservative Government you didn’t vote for falls away, along with the new constitutional reforms.

In the meantime, let’s assume that because of these political difficulties there has been no significant movement in national sentiment in either Scotland or Northern Ireland.

But demographics are taking their course, so support for leaving the UK is rising. And in Scotland, it’s now not far off the point where a ‘generation’ has actually passed since 2014.

In this scenario, the 2030s could see a winner-takes-all contest for the future of the UK, with the middle ground nowhere to be seen.

That’s why what happens in the rest of this decade could be the last chance for reform.

Conclusion: the case for reform, and making it

So what might reform involve? Here are some brief concluding thoughts.

First, there are plenty of areas where there is scope for imaginative reform.

Issues like immigration and trade need to be settled on a UK wide basis but there is no reason why there cannot be mechanisms for greater consideration of interests across the UK in setting those policies.

The fiscal frameworks are less lopsided than they were when they were designed in the 1990s, but they still contain many disincentives for the devolved nations to use the powers they have.

The mooted ideas for rebalancing the upper House might gain traction.

In the other direction, surely we might learn from Covid about how better to coordinate crises – that might even mean understanding when it makes sense for Westminster to take some powers back in return for better consultation and coordination with devolved administrations about how to use them.

There is much still to explore in terms of how the governance of the UK works.

Second, meaningful reform must contain some proposals for agreeing a mechanism on how the constituent parts of the UK can leave if they want to.

The position in Scotland is unsustainable: if the pursuit of independence is regarded as a legitimate political pursuit, then a way of achieving that must be provided.

At present, there is no such mechanism.

Third, the process matters. This cannot any longer be a conversation among the non-English parts of the UK only.

But this is really, really hard.

England cannot forcibly be decentralised or broken up into regions it doesn’t recognise.

England resents when the other nations are seen to be able to dictate their place within the UK.

Again, there are no easy answers.

Can, for example, any of the suggested changes to the upper chamber be done in a way that strengthens non-English nations’ role in UK wide life but is done in a way that commands England’s consent?

And now to the most important points.

Penultimately, is there a way of making changes permanent and enduring? I know Sir David Lidington, in an earlier address in this series, dwelt on this topic.

After a contested Brexit, and with the renewed strength of sovereignty-first British nationalism, many, including me, will be sceptical about the durability of any reforms beyond the lifetime of the Government that introduces them. I was no great fan of the Fixed Term Parliaments Act. But its fate is a reminder of how temporary constitutional reform can be.

Is there actually a way of ensuring the permanent powers of national institutions outside England given the doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty?

That question is also really, really hard. But it is really, really important.

So serious, impactful, enduring reform will be difficult. And it could be the last chance.

But, my final point is that if these problems can be overcome, then their advocates should make the case for the reforms as a something good in their own right, not as a concession. .

If you think the UK is better governed as a multinational state under messy but workable arrangements, rather than in a singular, Anglocentric British nationalist way, then say so.

For too long the decentralisation of power outside England has been presented defensively: the ‘Vow’ to Scotland in the dying days of the 2014 campaign being the most obvious occasion.

Contrast that with where I started.

The 2012 multinational union, comfortable in its multinational diversity, presented to the world in the Olympics had much to commend it.

Wales is perhaps uniquely suited to this proposition.

Its devolved arrangements have secured the consent of the many who did not originally want them.

It has the only devolved Government that can convincingly go to London saying it wants to make the UK work, even if political leadership is different.

Wales has a vibrant, non-political national life, shown by, among other things, the remarkable resilience, and now expansion, of the Welsh language.

Again, from an outsider’s perspective, if anywhere is to make the case for a thriving, multinational, reformable state, it is probably Wales.

So reformers should make their case.

In 2016, pro-Europeans found that if you’ve spent years presenting something in negative terms, boasting instead about how successfully you’ve used it to resist something else, then don’t be surprised when people aren’t particularly enthusiastic when you ask them to endorse it in its own terms.

If you’ve taken the trouble to work out how to do it, then make the case for it. If you believe in a devolved, respectfully multinational UK, then make the case for it in its own right, not as a way of stopping something else.

Thank you for listening to me this evening.